The Flying Eagle cent holds a unique place in American history. Unlike later cents, the Flying Eagle was not intended as a long-term solution. It was a transitional coin, introduced during a period of experimentation at the U.S. Mint. That short lifespan is a major reason that makes it one of the most valuable pennies to exist. Collectors continue to study and pursue the series today.

Why the Flying Eagle Cent Was Created

By the early 1850s, large copper cents had become increasingly unpopular. They were heavy, costly to produce, and often rejected in everyday transactions. At the same time, copper prices rose sharply, squeezing the Mint’s margins.

Several developments pushed change forward:

- Rising metal costs made pure copper cents impractical

- Public resistance to large, thick coins grew stronger

- Foreign copper coins still circulated widely, creating confusion

- Mint reform efforts aimed to modernize U.S. coinage

Congress authorized a smaller cent made from a copper-nickel alloy. This reduced intrinsic value while maintaining durability. The new alloy also gave the coin a lighter color, immediately distinguishing it from earlier issues.

James B. Longacre and the Design Break

Chief Engraver James B. Longacre was tasked with creating the new cent. Instead of adapting existing motifs, he introduced a dramatic new obverse: an eagle in full flight. The image drew inspiration from Longacre’s earlier work on the Gobrecht silver dollars, where a soaring eagle symbolized national progress.

The reverse featured a wreath encircling the denomination, a familiar element meant to balance the modern obverse. On paper, the design looked promising. In practice, it proved difficult.

The high-relief eagle clashed with the wreath during striking. Metal flow issues caused weakness in key areas, especially on the eagle’s head and wing tips. These technical problems would ultimately limit the coin’s lifespan.

The 1856 Pattern: A Coin That Wasn’t Meant to Circulate

The first Flying Eagle cents appeared in 1856, but not as regular circulation coins. Approximately 1,800 pieces were struck as pattern issues. These coins were distributed to members of Congress, officials, and influential collectors to build support for the new cent.

Despite carrying a face value of one cent, these patterns reportedly sold for around two dollars almost immediately. That price alone signaled strong collector interest, even before official circulation began.

Several characteristics define the 1856 issues:

- They were never released for general circulation

- Many survive in high grades due to careful handling

- Minor varieties exist, including repunched dates and leaf details

- They remain the most valuable coins in the series

Today, even lower Mint State examples command five-figure prices according to auction data from the Coin ID Scanner App. It reflects both rarity and historical importance.

A Transitional Coin With Lasting Impact

The Flying Eagle cent solved some problems but introduced others. It successfully reduced size and metal cost, setting the template for future small cents. At the same time, its striking difficulties highlighted the limits of certain artistic choices in mass production.

This tension between innovation and practicality defines the series. Collectors value the Flying Eagle not just for rarity, but for what it represents: a moment when U.S. coinage took a decisive step toward modernity, even at the cost of short-term complications.

Circulation Years, Varieties, and the End of the Series

After the experimental success of the 1856 patterns, the Flying Eagle cent entered full circulation in 1857. This marked a turning point in U.S. coinage. For the first time, Americans exchanged bulky large cents for a lighter, modern alternative. The transition happened quickly and at a scale never seen before.

1857: The First Circulating Flying Eagle

On May 25, 1857, the U.S. Mint began exchanging Flying Eagle cents for old large cents through banks and Treasury offices. Public response was immediate. The smaller size and lighter weight proved far more convenient, and large cents disappeared from circulation rapidly.

Production reached approximately 17.4 million coins, making 1857 the highest single-year output of any U.S. cent up to that time. Despite the large mintage, many pieces circulated heavily, and well-struck survivors are far scarcer than the numbers suggest.

Collectors today look for:

- Strong feather definition on the eagle

- Minimal weakness on the head and wing tips

- Clean surfaces free from corrosion or cleaning

In circulated grades, values typically range from $400 to $1,000, depending on eye appeal (better use evaluation via the coin value app). The series also gained early collector attention through hoards, most famously the George Rice accumulation of 756 pieces, which helped shape early market activity.

1858: Design Adjustments and Varieties

By 1858, the Mint attempted to correct some of the design and striking issues. Two major obverse styles emerged, creating a clear split that defines the final year of the series.

Large Letters vs. Small Letters

The distinction appears on the reverse. Large Letters coins show bolder text and a slightly wider wreath, while Small Letters pieces have more delicate lettering and tighter spacing. Both types circulated, but collectors treat them as separate varieties.

Key points for each:

- 1858 Large Letters: Higher initial production, often weaker strikes, values around $400–800 in VF

- 1858 Small Letters: Lower mintage, sharper appearance, typically $500–1,000 in VF

Advanced collectors often pursue both, focusing on strike quality rather than date alone.

The 1858 Overdate (8 Over 7)

One of the most significant varieties in the entire Flying Eagle series is the 1858 8/7 overdate. A previously punched 1857 date was re-used, leaving traces of the underlying “7” beneath the final “8.”

This variety is scarce in all grades and highly sought after. In Very Fine condition, examples often exceed $3,500, with sharp pieces climbing much higher. Correct identification requires careful magnification and familiarity with the diagnostic remnants of the earlier digit.

Why the Flying Eagle Failed Technically

Despite strong public acceptance, the Flying Eagle cent was difficult to strike consistently. The combination of a high-relief eagle and a dense wreath reverse caused repeated metal flow problems. Dies wore quickly, strikes weakened, and quality control suffered.

The Mint concluded that a new design was necessary. James B. Longacre responded with the Indian Head cent, which debuted in 1859. Its lower relief and more centralized design solved many of the issues that plagued the Flying Eagle.

By the end of 1858, the Flying Eagle cent was gone from production, replaced after just two years of circulation.

| Date / Variety | Mintage | Typical VF Value |

| 1856 Pattern | ~1,800 | $10,000+ |

| 1857 | 17.4M | $400–1,000 |

| 1858 Large Letters | 24.7M | $400–800 |

| 1858 Small Letters | 17.8M | $500–1,000 |

| 1858 8/7 Overdate | Unknown | $3,500+ |

These numbers highlight the paradox of the Flying Eagle cent: high mintages paired with low survival in quality condition.

Collector Strategies, Grading, and Long-Term Appeal

The Flying Eagle cent rewards careful selection. Its short production run attracts collectors, but condition and authenticity determine long-term value. Many surviving pieces show weakness, wear, or past cleaning. Knowing what to seek—and what to avoid—makes a significant difference.

What Collectors Should Prioritize

Flying Eagle cents circulated heavily and were struck with technical limitations. As a result, truly sharp examples are scarce. Collectors often focus less on the date and more on strike quality and surface preservation.

Strong candidates typically show:

- Clear feather separation on the eagle’s wings

- Definition around the head and neck

- Even coloration without harsh cleaning

- Minimal clash marks or die fatigue

Coins graded AU and higher offer the best balance between affordability and visual appeal. Mint State examples command strong premiums because relatively few survived with full detail.

Grading Considerations

Grading Flying Eagle cents requires experience. Weak strikes can resemble wear, especially on the eagle’s head and upper wings. This makes third-party certification valuable for higher-end pieces.

Certified examples from PCGS or NGC often sell at 20–50% premiums over comparable raw coins due to market confidence and population transparency. That premium reflects both authentication and liquidity.

Collectors should be cautious with raw coins advertised as high grade. Signs of cleaning—unnatural brightness, hairlines, or dull surfaces—can cut value dramatically, even on scarce varieties.

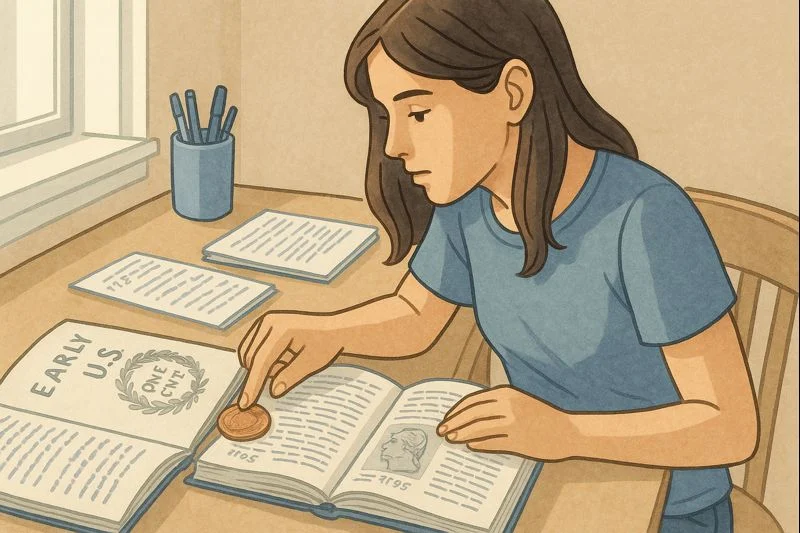

Authenticity and Varieties

The 1856 patterns and 1858 overdates attract counterfeit activity due to their price levels. Authentication matters most with these issues. Studying diagnostics and comparing verified examples remains essential.

During estate reviews or coin show searches, some collectors use tools like the Coin ID Scanner app to quickly confirm basic specifications such as minting years, composition, diameter, and weight. Its photo-based identification helps flag potential Flying Eagle cents that deserve deeper examination, especially in mixed or poorly labeled groups.

The Flying Eagle cent remains popular because it represents change. It marks the end of large copper cents and the beginning of modern U.S. centage. Its design is bold, its history compact, and its survival uneven—qualities that continue to attract serious collectors.

Values have remained resilient over time, especially for well-struck examples and recognized varieties. While the Indian Head cent followed more successfully, the Flying Eagle stands apart as an ambitious experiment that reshaped American coinage.